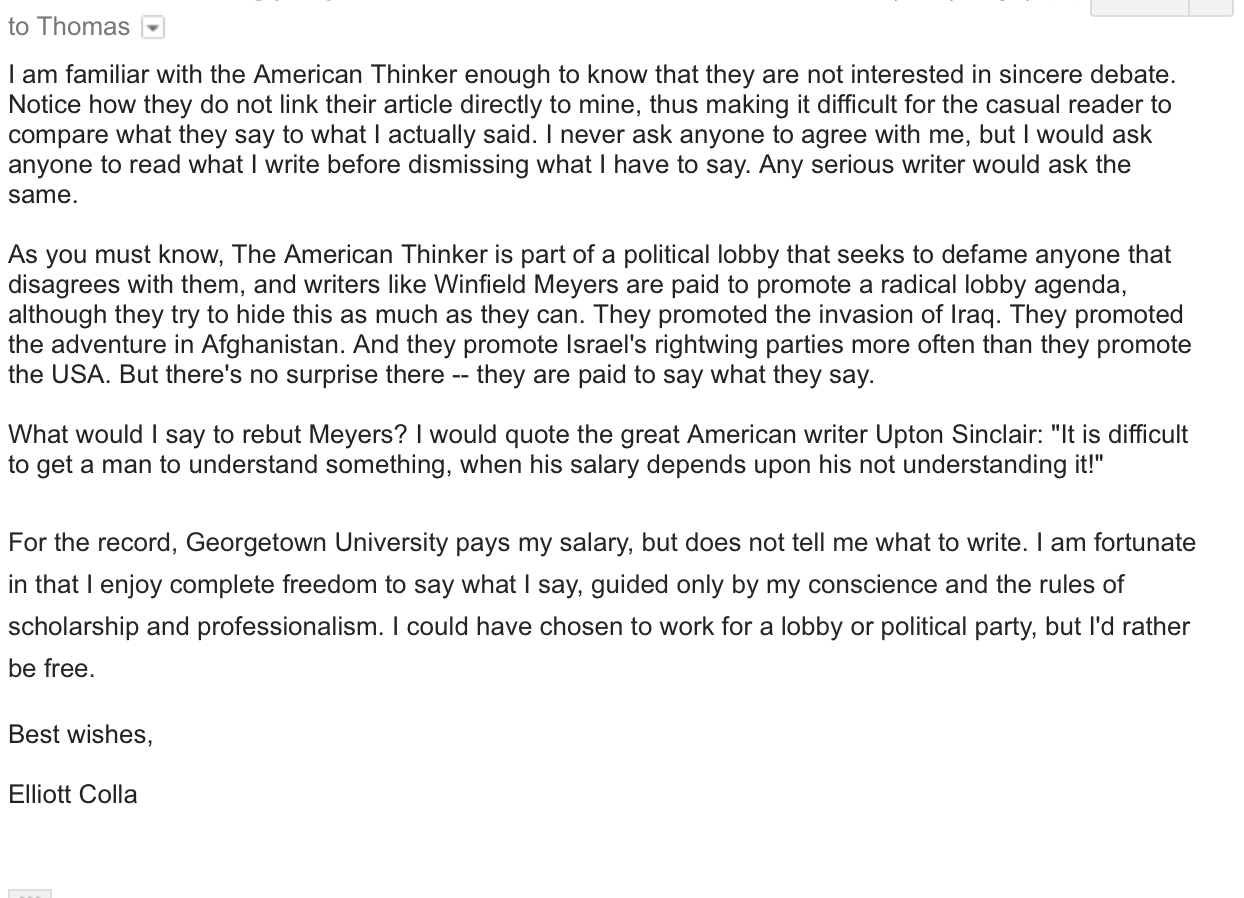

It is exceedingly difficult to know "what to do" as ISIS continues to attack the ancient material culture of Iraq and Syria. A few months ago, I weighed in on the subject in an essay that suggested that those of us who value antiquities for their historic, scientific and aesthetic value would do well to reflect on the ironies of the situation.

One of my main theses, which would be non-controversial for students of history, was that there is nothing inherently "Islamic" about the particular form of iconoclasm (or vandalism) practiced by ISIS. Throughout Islamic history, Muslims have held a wide range of beliefs about, and engaged in a wide range of practices involving, the objects of pre-Islamic antiquity. These range from admiration and wonder to indifference and doubt. The same range of attitudes exists in other traditions.

Admittedly, I could have focused on the specifically "Islamic" elements of ISIS's campaign, which is to say, how they belong to a modern, Wahhabi tradition of attacking artifacts said to belong to other pasts. This tradition, while "Islamic" in the sense that its Muslim proponents practice it in the name of "Islam," should be seen for nothing more or less than what it is: a strategy of projecting, in brutal and spectacular ways, the material and cultural power of a nascent jihadi state. When viewed against the backdrop of 1400 years of Muslim cultural attitudes toward the distant past, it is a remarkably bleak aberration, though not one without precedents. The more dominant intellectual and textual traditions looked at the past as something to learn from, not something to destroy. Which is to say, ISIS's attacks on Palmyra have their roots not in the Qur'an or Hadith, but rather in the cruel 18th- and 19th-century Wahhabi-Saudi campaigns against tombs and Sufi shrines in the Arabian Peninsula as well as sites of Shiite veneration in southern Iraq.

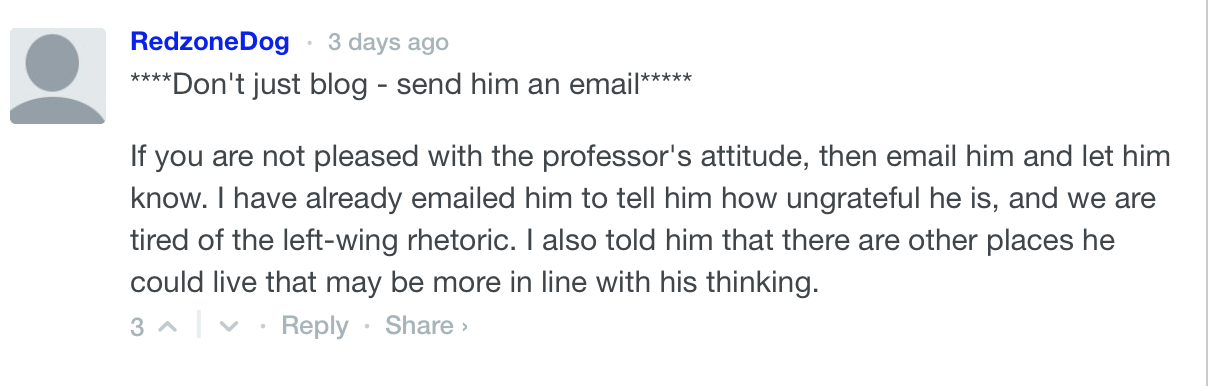

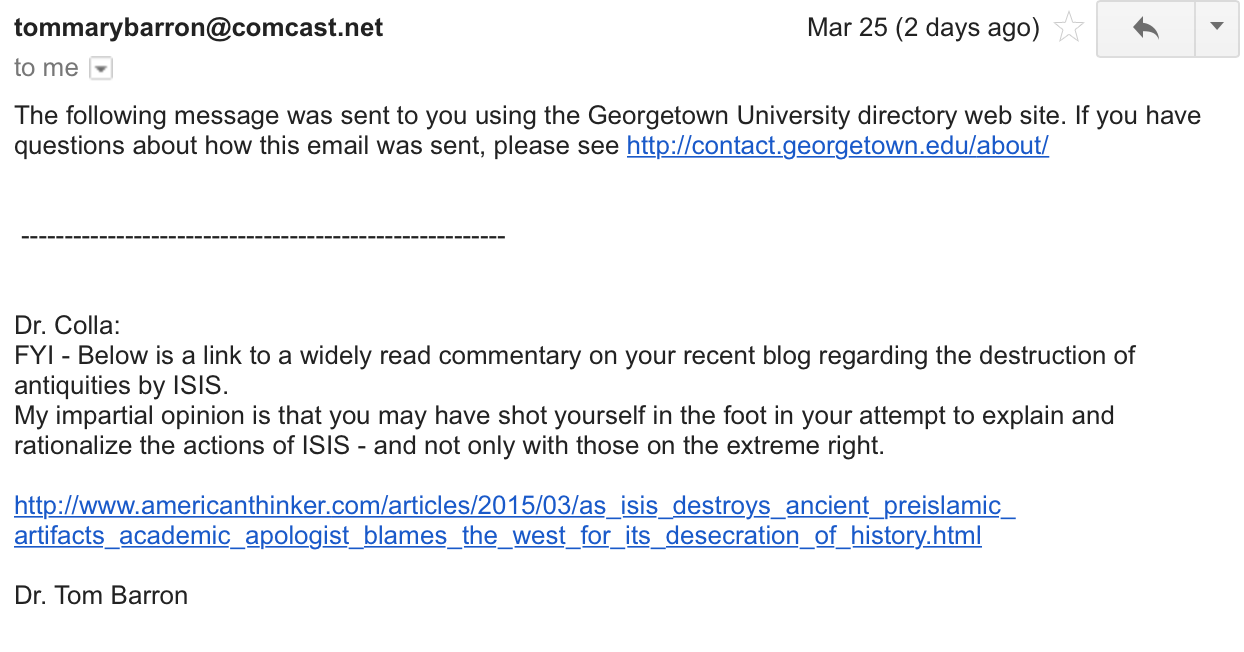

Similarly, my blog post could have focused on ISIS's iconoclasm as a problem inside Islam, insofar as the Wahhabi-Saudi state theology really is a problem within Islam. But it did not because, as an American, I have a greater responsibility to respond the problems of my own national community, and in this case, the disingenuous posturing of neocons and their liberal allies who, in decrying the destruction of things, call once again for more US military intervention, as if that could be a solution. Contrary to what was said about my piece by interventionists, my piece did not seek to defend ISIS or attempt to rationalist its abhorrent actions. Similarly, there was nothing in the piece seeking to argue that the toppling of cheap Baathist-era statues was the equivalent of destroying priceless ancient artifacts. There was a juxtaposition of images of toppling statues meant to suggest that similar military logics were at work: destroying the arts of the defeated is what triumphalists have always done. If reckless interventionists were bothered by that suggestion, then all the better.

In the main, my post tried to shed light on the deep hypocrisies at home that have become, since ISIS's emergence, more and more manifest.

The first hypocrisy is a disjointed form of American compassion marked, on the one hand, by newfound concern regarding Mesopotamian objects and on the other, a longstanding indifference toward the suffering of Iraqi people.

The second hypocrisy is rooted in the failure to recognize that the current moment of looting and destruction belongs to a historical context where the US military figures prominently, sometimes as an enemy of antiquities preservation and sometimes as its incompetent champion.

The third hypocrisy has to do with the witting participation in mass antiquities thefts by Western and Gulf antiquities dealers and buyers over the last decade. Without their willingness to traffic in stolen artifacts, the looting would not have reached the scale it has.

ISIS’s attacks on antiquities, like its reported involvement in the illicit antiquities trade, come directly from these contemporary histories. This remains true, even as ISIS spokesmen hide behind pious invocations of anti-pagan, iconoclastic "traditions" that far from being age-old are in fact largely modern phenomena, invented often during protracted conflicts with Western military incursions.

Each of these hypocrisies is rooted in our culpability as American citizens whose democratically-elected governments and all-volunteer armies have been at war with Iraq and in Iraq continuously since 1991. It has been more than twenty-four years now since we first began our direct war against Iraq, killing hundreds of thousands of Iraqis in the process, laying waste to large swaths of the landscape, and destroying—through harm and negligence—massive amounts of the country's cultural heritage. In this context, it is ridiculous for commentators to seek explanations of ISIS’s actions in seventh-century Meccan history or tenth-cenury Quranic commentaries while ignoring the well-documented rise of mass looting and theft that occurred during the US occupation and as a direct result of Washington's policies. Likewise, it is disingenuous for American commentators to imagine that the US was merely a distant spectator as Baathist thugs turned into pious Islamists during the years of US-led sanctions, and, during the years of US military occupation, a network of militants were gathered together in US prison camps and eventually morphed into ISIS.

In my blog, I did not comment at length on the depth of the crisis and what it has meant for archaeology and museums. Other commentators, like Fred Bohrer and Ömür Harmanşah have brought these points home in powerful ways. Nonetheless, let it be stated explicitly: anyone who cares about the past should be distraught, troubled and astonished by ISIS’s wanton destruction of museums and archeological sites. The materials under attack are nothing less than the priceless patrimony of Iraqi society, and perhaps something called humanity, if such a thing exists. In some cases, these objects under attack are the only surviving material culture we have of ancient eras of human history, and their value to the study of our own human development cannot be overstated.

Is there any debate as to whether these objects deserve to be conserved in order to be studied by people trained to study them? There shouldn’t be -- but apparently since I did not repeat my allegiance to the principles of conservation explicitly, it was assumed I was against them. But my point wasn't to confirm a widely-embraced truism. Rather it was to question whether the only solution to this crisis was to pour more US bombs on it. I did this by attempting to problematize the way antiquities figure as important material signs in our modern, still-colonized world, and that as signs, antiquities can be used to mobilize senseless violence.

Affective Attachments

It is a truism that talk about artifacts often slips into talk about civilization. The slippage is common because it was intended to be. And because it is taught to some of us from a very early age. For example, the image or even silhouette of an ancient monument is usually enough to suggest a cultural, even spiritual meaning that far transcends the material dimensions of the object itself. The great pilgrimages that people make in order to be in the presence of artifacts unearthed by archaeologists is another indicator of the expansive meaning these objects have. A visit to the Parthenon or Jerash is for many an occasion to dwell in the presence of something that goes beyond the rocks themselves. It may be awkward to call monuments sacred or the modern veneration of antiquities a form of modern, secular religion, but I can think of no better terms that capture the sense of transcendent value, and the rituals of adoration that accrue around such objects.

From here, it is but a short step to the notion that an attack on such an artifact is an attack on civilization itself. This is precisely where caution and critique are most needed. Why? Because this slippage from material object to moral argument has a genealogy, and a history.

The affective attachments linking material objects to broad, moral claims about civilization are not natural but constructed. To point this out is not to suggest that they are unreasonable or undesireable, but rather that they are the result of human activity. Which is also to say, they emerge in histories of struggle, both as terms of struggle and as sites of struggle.

In my own study of a separate history of struggle over antiquities in Egypt, I found that the colonial context of archaeology marked the scientific and humanistic study of the objects in indelible ways. The history of archaeology and museums in modern Iraq is different, and yet it is marked by similar processes. For instance, in Mesopotamia, as in the Nile Valley, the great discoveries of colonial archaeology profoundly, and often negatively impacted the land rights, labor markets and local cultures of indigenous peoples. Similarly, in Iraq as in Egypt, those who most championed the civilizational meanings of ancient objects also tended to voice the most racist views about the modern inhabitants of ancient lands. Antiquities policies were built on these racist views, and it mattered to the people whose lives were impacted. (And as Nadia Abu El-Haj showed, the impact of Zionist archaeology on Palestine was even more pronounced.) While the move to nationalize the professions of archaeology and museum curatorship overturned and corrected some aspects of this colonial legacy, it also compounded them in other ways. Peasants, for instance, continued to be imagined primarily as a problem in the preservation regimes of the nationalist period just as they were during the colonial era. Scholars of colonial and nationalist archaeology have noticed similar patterns in the region, in Palestine, Iran, Turkey and elsewhere.

These dynamics are well known by those of us who study the region’s history, even if there is wide variation about how to interpret their meaning. Moreover, it is not just students of Middle Eastern history who have tried to grapple with these legacies: across the archaeological disciplines, similar lessons have been learned by a generation of post-processualists who have struggled to make ways for local populations to participate in the interpretation and conservation of ancient artifacts. And yet, as the present moment reminds us, colonial-era moral claims about civilization still dominate discussions about antiquities.

Artifact Interventionism

Many commentators on ISIS’s actions have pointed to a range of other historical contexts of iconoclasm—Revolutionary France, Byzantium, Bamiyan—with resonances to our moment. These analogies are rich in some ways, but they seem to miss one powerful fact—namely that ISIS is very aware of the kind of response its actions will garner and this, perhaps more than its rather inarticulate destruction of the objects themselves, seems to be the point. The destruction of the material objects is central to the story, but it also matters that these event are scripted and staged for the camera, and then mounted onto global media platforms as a spectacle assured to provoke intense reactions.

As suggestive as the history of iconoclasm is, and as tempting as it is to imagine the motivations of ISIS iconoclasts, we should not fail to notice that the perpetrators of these crimes understand, or hope, that their actions will trigger intervention. To understand this, we need to situate these events within a history of artifact interventionism.

What is this history? In the nineteenth century, some of the first calls for direct European military invasion in the Arab world took place in the following way: a traveler or diplomat observes that an area is rich in ancient artifacts; the writer claims that such artifacts are under threat by the actions of local populations; using moral arguments about civilization, the writer urges his government to save the artifacts, employing military force if necessary; months later, the artifacts appear in the metropolitan museum. The process, to paraphrase Gayatri Spivak, is one of “white men saving antiquities from brown men.”

In the twentieth century, as colonized states won qualified forms of political independence, the terms changed slightly. Whereas in the colonial past, Western archaeologists had sought the protection of strong colonial governors, in the postcolonial era, archaeologists tended to favor strong autocratic local regimes because they believed that such regimes were more stable and thus better for securing exploration, excavation, and preservation. In this regard, we might consider the popular perception that many Egyptologists were glad when General Sisi came to power and they could finally get back to work. If true, this too would need to be seen as another variation on the old theme of antiquities interventionism.

By invoking this history as relevant, I am not claiming that all calls to preserve objects from attacks are spurious, nor am I saying that all champions of conservation are warmongers or enablers of dictatorships. The reality is more complicated than that. As the current response of archaeologists and museum curators to the ISIS emergency shows, preservationism is complex, creative and often self-critical.

Nonetheless, this history must be part of the conversation (and it is in some circles) since historically, many of the most urgent calls for preserving antiquities have served as the prelude to (and rhetorical grounding for) military intervention. And it is this history—as much as the intricacies of iconoclasm as a recurring historical theme and practice—that seems so relevant to our moment.

I doubt whether ISIS iconoclasts know much of this history, just as their command over the textual traditions of Islam is so widely doubted. But they do not need to know any of this history to understand that an attack on a cultural icon revered in the West will shock elite opinion in the West, and thus enable broad tolerance for intervention among people who might be otherwise averse to military adventurism. ISIS strategists bet that their attacks will mobilize our own extremists—those who have called for open-ended military assault for many years now—thus provoking the kinds of conflict that help them recruit more jihadists.

After Bamiyan, Charlie Hebdo, the Mosul Museum and Palmyra, it should be clear that there is a broad, jihadi strategy to bait the West, staging crises where something civilizational needs saving. ISIS does not need a Quranic verse or fatwa to tell them to attack artifacts and art, for the simple reason that they already know there will always be white men who volunteer to save civilization from brown men. Again, this strategy is not grounded in any supposed theological aversion in Islam towards the image or the pagan past, but rather in a bloody colonial inheritance whereby national liberation has degraded into a logic of 'trading dead bodies', as Faisal Devji put it in his 2009 book, Landscapes of the Jihad. Juan Cole has talked about this same strategy in terms of “sharpening contradictions.”

Beyond Colonial Rhetorics of Civilization

Many of the loudest voices calling to protect the objects have never shied away from the call to defend civilization from barbarism. Likewise, many even parrot nineteenth-century antiquities interventionist rhetoric, calling for boots on the ground to secure objects on the ground. The civilization-barbarism binary is objectionable not just because it is historically inaccurate, but also because, when made into policy, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

It is not an accident that many of those now calling for the defense of civilization against the attack of ISIS were the same ones championing the US invasion of Iraq in the first place. This hypocrisy, as the use of moral discourse about civilization more generally, will only lead to more of the same.

So, what is to be done? Those who speak most forcefully for action tend to think that only one thing can be done: more US intervention. They say this, knowing full well that US intervention played an outsized role in creating the collapse of the Iraqi state and in fostering the sectarian politics of post-war Iraqi society, just to take two of the principle catalysts for the rise of ISIS. Similarly, US military intervention played a direct role in the collapse of an already fragile Iraqi antiquities conservation system, and in the rise of new markets for looted artifacts. I have no doubt that the proponents of US intervention could produce examples of when the US military helped to secure particular excavation sites—but these, I think, are exceptions that prove the rule. And so perhaps it is easier to begin by saying what should not be done. Repeating past mistakes, for instance, is something we should not do, no matter how much we are provoked by the crimes of ISIS. Imagining that somehow this time, US military intervention will be different is another thing we should not do.

Long ago, Homi Bhabha reminded us of the ties between ‘emergency’ and ‘emergence,’ in order to suggest that crises are also opportunities for the emergence of something different. In that spirit, here’s a thought: what if, instead of responding to this emergency with more bombs we were to work toward producing more democratic, inclusive and effective systems of preserving antiquities? Forms of conservation and study built not on threats of violence, but rather on equitable participation in discovery and conservation as well as a transparent and fair distribution of resources? If it is justice that is desired, we could more consistently and vigorously enforce already-existing laws that ban the traffic of looted artifacts. While we're at it, if we are truly outraged by the destruction of Mesopotamian artifacts, we might even begin to hold those American officials legally accountable for the negligence and malfeasance of the occupation of Iraq, especially actions those that set in motion the waves of looting.

Reasonable critics might say that is fine, but such things involve decades of education, inclusion and building and that right now we have an emergency on our hands. To them we should say: this has always been the case. Moreover, military intervention is not so much a solution to the destruction of antiquities, but one of its causes. Since Napoleon's intervention to save Egypt from the Ottomans, there is always an emergency and there has always been a crisis, and the great patrimony of human civilization is under threat. These things are related to one another in direct ways. And in the meantime, this greater work of education, inclusion and building is always postponed.

If we could move past the military incursions of the past, and past support for local strongmen promising security, we might finally attend to these larger and nobler tasks, which means we might have a chance to preserve the past and also learn from it. Anything less is the real threat to the patrimony of human civilization.

![Maigret statue in Delfzijl. [Image from wikipedia]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52dc0cc7e4b0e34b862ece81/1424024543392-WXV796W8C9VJN0LZR8HE/image-asset.jpeg)