In January 2007, the NYTimes went in search of examples of how professors give exams in the field of Middle East Studies. This is what they got. I like the exam I submitted to them, though I can admit it now: mine is an example of an exam I'd love to give, not an exam I've ever actually administered. And for the record: multiple choice exams have as much place in a literature curriculum as a scantron exam has in your DVD player.

Tea with Mint: A Conversation with Zein El-Amine

A couple weeks ago, Zein El-Amine invited me over to talk about translation and writing from and about the Arab world on his show, Shay-wa-na'naa' (Tea with Mint), on WPFW (89.3 in the District). This lovely, rambling conversation is what happened next.

Ahmed Douma: Two Poems

Like hundreds of other prisoners of conscience now languishing in Sisi's prisons, Ahmed Douma has a long background in activism. One of the founders of Kefaya and the April 6 Youth Movement, Douma was incarcerated eighteen times under Mubarak and SCAF and twice again during Morsi’s brief year of rule. Most recently, Douma was arrested in December 2013 for violating the country's harsh anti-protest laws. Though his health has deteriorated to the point that his life is now at risk, an Egyptian judged recently sentenced him to three years in prison.

Forgotten in all this is that Ahmed Douma is also a poet with an original voice. His diwan, Sotak tali3 (Your Voice is Rising, Cairo: Dawwan, 2012) is a remarkable document, wholly unknown in English. Here are two poems from it:

1. IF ONE DAY THE PEOPLE

If one day the People wills to live,

Then they can go revolt.

And the echo of their songs can chase away palace dogs

And they can raise their banners whose cloth has been dragged in the dirt

Dragged through streets, servility and surrender.

And they can turn those banners into a plan of attack

And hang the darkness of their night on the gallows.

While the dreams of their night tremble

At a spark flickering in the heart

At a light…

If one day the People wills to win,

Then decision must dictate

That silence is no longer an option

And they must create, with their own hands,

Daylight rays for the sun of emancipation!

They must help give birth to a country, as yet unborn

Struggling midwife,

Pulling the country hard and harder,

Shouting out in its ear the call to prayer, “Revolution has risen!”

And “There is no revolution but the Revolution you make yourself!”

Let our country nurse on the many meanings of dignity.

Let it come to know how to break the siege.

If one day the People wills to arrive at its destination,

Then it has no choice but

To gather the ammunition it will need for the journey

To call what lies between us and them

The length of countries

Saying, “You sons of…”

Its time for the Dog to go.

Enough with the howling.

Enough with the voiceless shrieking.

Enough with death.

The People opens their eyes and finds their guide

They see that the one who betrayed them

No longer exists.

In their victory, they cross bridges and borders

Shrieking

And shrieking,

Shrieking and shrieking.

I am now free.

Without shackles.

Now I am free, without chains.

If one day, the People wills to live,

Then they must learn to break their chains themselves.

(Midan Tahrir, May 2011.)

2. DEMONSTRATION

Police cordon, police cordon

Dog and guard,

Black, black, black

Is your uniform

Street front, war front

En-e-my

This is the youth of our country!

One hundred bosses, one hundred chiefs,

And countless gentlemen, epaulets stuffed with eagles

The stars of their insignias rising

In the middle of the afternoon

Spreading fear in pure hearts,

Spreading insults about my mother and my mother’s mother,

And the person who gave birth to you and me,

And the living and the dead,

Religion too, and that dog unashamed

(definitely a ranking officer)

Spewing every cussword in the book.

Now, in the middle of the square, the bloodbath begins.

And out, into the light, injustice arrives,

Electric cattle prods,

Tear gas, whose stench creeps toward us.

Beatings all around.

The best and the brightest are there in the fray,

There is no escaping death.

You either die here or there

Or you can die for the country as it slips from our grasp

As it falls into ruin’s embrace

And you, and your country, wherever you run,

Will find nothing but police cordons around you.

The fighting still going on, uninterrupted

There is no difference between boys and girls,

They insult her while bashing in her head

With fists.

While the son of a bitch just stands there, smiling

Saying, “Bring them here. Drag them over.”

They beat the pulp out of them

Then send them off in cuffs to get booked.

Go ahead and hurt us,

But don’t forget to cry about it,

Or say, like kids in the playground, “Those bullies hit us,

And kicked us around,

Even though we were there to protect them.”

In the charges they write: The assailants

Had written the word Enough on their clothes

They were waving the flag

Claiming that the country

For twenty-five years has been robbed

Looted, and oppressed.

They insult the dear King,

They claim

He is a despot

And fit to be tried in court.

All rise and be silent.

Only the judge has the right to speak.

The defense rises, the accused, the prosecution.

The press will broadcast the ruling,

When it has been pronounced

The defense is not allowed to speak,

The defendant is guilty

And the judge pronounces it loud,

In the name of the magnanimous ruler of this country,

Each of these dishonest demonstrators is to be imprisoned

Justice has died in Egypt.

Those who displease the regime

Receive open-ended sentences

That might go on to the end of time.

Only a revolution against all shackles

Can break them.

Only that can restore Egypt’s glory.

Revolution is coming.

Despite the cordons,

Light will shine.

Despite the blackness

Of their uniforms, of the warfront streets

And the enemy: this country’s youth.

Down with every police cordon.

Down with every cordon

(Qasr al-Nil Jail, May 2010)

Originally posted at Mada Masr

"Ahmed Douma" photomontage, © Johann Rousselot (image from: http://www.loeildelaphotographie.com)

Buying Books in Cairo

[Tomorrow night, I will be joining a distinguished panel of poets, activists and scholars speaking about poetical and political freedoms at George Mason University's Fall for the Book festival. This is part of an ongoing DC-wide effort to contribute to the Mutanabbi Street Starts Here DC Project. Rather than give "analysis", I thought I would talk about poetical and political freedoms by way of my relationship to the book markets of Cairo. This is what I will read tomorrow night, though more in the style of a slide show. See you there! Here's a version in Italian.]

September 1985. My first year as a student in Cairo. I visit Cairo’s main book market located in the famous area of Ezbekiyya. When Napoleon tried to conquer Egypt, this was the site of a man-made lake surrounded by the ornate palaces of Turkish Pashas and high-ranking officials of the late Mameluke state. A century later, during British rule, the lake had been filled in and the area converted into a vast entertainment district. Bars and theatres, cabarets and brothels catered to Cairo’s elites who met in this border zone located between the medieval casbah and the new colonial downtown. By the time I get to Cairo, most of this history has disappeared under flyovers and Soviet-era concrete projects. Still, a few sordid belly-dance clubs still hold out over near the decrepit old fire station and post office.

The book market is literally fastened to an old black iron fence. Inside the bars, sit the stately gardens of Ezbekiyya Park, completely off-limits to the general public. Outside, the book market stalls cling to a tiny strip between the fence, a chaotic bus depot, and the busy streets of Ataba.

I do not read Arabic in 1985. So, I mostly look around at the posters. During those years, most of them featured the Indian beefcake actor, Amitabh Bhachchan and a woman provocatively fixated on a snake, her full red lips about to kiss it.

Among the piles of used books, I find heaps of English-language books. Most are those cheap simplified editions of classics—like Wuthering Heights and Great Expectations—that fill the markets of former colonies. I find a scientific treatise entitled, Spontaneous and Habitual Abortion. The seller tells me it costs 25 piastres, maybe about 5 cents. I mumble something in pigeon Arabic and put it back, the bookseller smiles. I go back often that year.

November 1989. The Berlin Wall has fallen or is falling. Around then, the book market is removed from the fences at Ezbekiyya, during the building of the Midan Opera Metro Station. It is hard to tell whether anyone noticed. It is hard to tell if anyone cares.

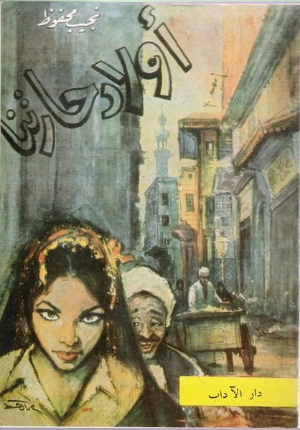

Everybody tells me I need to read Naguib Mahfouz’s novel about the death of God. The only problem is that times and mores have changed since Awlad haritna was first published. The novel originally came out in the Friday sections of al-Ahram in the late 1950s. Now it is banned in Egypt, deemed controversial and un-Islamic.

Everybody tells me that I can find the novel if I go to Madbuli's Bookshop in Midan Talaat Harb and ask for it discreetly. I go there and linger suspicious around the various sections of the bookstore. It’s like I’m looking for porn. Different employees come to ask if they can help. Finally, I gather up the courage and say, “They tell me you have copies of Awlad Haritna.” The man doesn’t even look at me. He mutters, “They’re wrong, whoever 'they' are,” and he keeps dusting the pile of books in front of him.

June 1990. The cold war is over, but Saddam Hussein has yet to invade Kuwait. I still want to find a copy of Mahfouz’s novel. I go back to Madbuli’s one afternoon. As soon as I enter, a skinny young man about my age asks if he can help me. I casually mention the title, and say nothing else. He disappears into the back and emerges with a book in a plastic bag. “Anything else?” He smiles at me. For the next 23 years, Ashraf becomes one of the first people I see whenever I return to Cairo. For the last six years, he makes a point of always asking about my daughter, even though he has yet to meet her.

February 1991. The new world order has begun, and three Cairo University students are killed protesting Mubarak’s decision to lend support to American troops. During these months, I have a standing date on Friday afternoons to meet a friend, Ahmad. We meet at the used book stalls just off Midan Sayyida Zeinab. I begin to find lots of books I need for my studies. I find a complete run of the literary magazine Fusul. And lots of old issues of al-Tali‘a. I find classics of literary criticism, 1950s editions when scholarly publishers like Dar al-Ma‘arif had editors. Ahmad and I wander among the stalls for an hour or so, then go off to a café just off the square where we discuss the reading he has assigned me for the week. For months, I have been reading Louis Althusser under Ahmad's tutelage. Later, when I return to graduate seminars in Berkeley, his lessons stand me in good stead.

January 1994. Cairo Book Fair. An annual event when all the publishers of the Arab world, and all the booksellers of the city, bring their wares out to a Soviet-era fairground for hosting industrial expositions in Medinat Nasr. It’s as cold and gray as ever, a day for drinking hot tea. I go out there with a group of leftist friends. We are all proudly wearing the same thick wool overcoats we bought in the outdoor market behind Ramses Station. Before we get there, Ahmed shows off the multiple hidden pockets his sister sewed into the lining. We spend the day wandering around the Moroccan publishers’ tables, where the most interesting stuff is being sold. Ahmed fills his pockets. We visit some of the salons where poets and critics and philosophers debate topics of the day. A group of Egyptian literary critics sit on a panel and discuss the Libyan Brother Leader’s collection of short stories entitled, The Village, the Village! The Land, the Land! We laugh as some critics talk about how sophisticated Qaddafi’s writing is. We wonder how much they were paid. We look around, but Ahmed is not with us. Later on, we learn he has been arrested for shoplifting. He tried to run away when they caught him, but his coat had more than 30 books in it.

June 1995. I find out that the Ezbekiyya book markets had been relocated some time ago back behind al-Azhar University, in the neighborhood of al-Bataniyya. In 1985, hashish was openly sold in the streets of Bataniyya, and was more affordable than beer. The sellers are gone now. To get to the used book market you can either enter from Harat al-Atrak, a small street filled with religious bookstalls, turning right toward the old city walls, now vast piles of medieval rubble. Or you can take a taxi to the end of Azhar Street, getting off at the Benetton, and walking to the right until you find the market. I find a treasure the first time I go there: an incomplete 19th century lithograph edition of al-Maqrizi’s Khitat. But the volume I need for my dissertation research is there. Because it’s incomplete, the seller subsequently negotiates a huge discount for me with the bookbinder.

March 1998. At some point, the Ezbekiyya book market has moved back to a newly renovated space in Ezbekiyya, back by the National Theatre. Friends introduce me to Mustafa Sadeq, a well-regarded book merchant in the market. We sit down and he listens to me as I describe the kinds of books I am interested in for a project on the representation of women and prostitution in Egyptian literature. Each week I come back, he has found a new pile of titles for me to peruse, most not related to what I am working on, but some very much so. He tells me he has a stash of books for me in his storehouse and invites me to come over there. It’s located in an alley in the Hilmiyya neighborhood, not far from where I used to study Althusser on Fridays.

Mustafa Sadek is waiting from me when I arrive. He rolls open the iron door and we step inside. He points to a stack of dusty old magazines and journals. I look at the first magazine and can’t believe it. I thumb through pages of erotic stories that are accompanied by photographs of naked women in suggestive poses. I look at the date on the periodical: 1934. I look at the next, same thing. And then more. Finally, I look up and find him smiling at me. “I know you are not only researching literature but also some impolite things,” he says with a sly smile.

The trove costs me every thing I had in my wallet, and still I owe Mustafa. On my way home, I go to meet Shehata —an Egyptian poet and novelist—for tea. I pull out all the nudie magazines I’ve just purchased and say, “Can you believe this?!” “I never knew this stuff existed,” he murmurs over and over. “This is an important source. We need to do something serious with this. Can I borrow this and show it to an editor. Together we might figure out a way to republish this as a historical document.” I wrap up the magazines for Shehata. We agree to meet up, as we always do, a couple days later. Shehata doesn’t come, and he stops answering my emails. Years later, when I finally see him again, he apologizes for disappearing. He was in the midst of a messy divorce. When I ask about the magazines, he claims he gave them back to me. I never see them again.

July 2002. Some old classmates from Cairo University have opened a great bookstore— Sindbad—located just behind the Cosmopolitan Hotel in the revitalized Bourse neighborhood. I go there and browse for hours. Despite its tiny size, this bookshop holds more treasures than the bigger stores around the corner. One afternoon, I am sitting with Abdel-Rahman S.—brilliant brother of the brilliant Muhammad S.—who is now not just a professor at Cairo University, but also one of the principal shareholders in Sindbad. He and his wife had just had me over for lunch a couple days earlier, and we’re sitting around talking while waiting for our old professor—Egypt’s leading left literary critic—to meet us there. The subject now, as before, is American imperialism and the efforts of Egyptian intellectuals and artist to boycott Israel. Abdel-Rahman’s rambunctious and precocious eight-year-old son is with us all afternoon, bored out of his mind, entertaining us by asking questions that go beyond his years. At some point, the kid starts referring to me as the “imperialist, colonialist American,” and everyone laughs. He disappears. Minutes later, Abdel-Rahman and I go out to find the boy. We watch him walking down the pedestrian mall pulling on an Egyptian conscript who had been stationed outside the bank on the corner. The boy points at me and calls out, “See! See! Fire! Fire!” The soldier doubles over in laughter, not able to believe his eyes when he sees the boy has produced the Zionist enemy he had promised. By the time we arrive, the boy has grabbed the soldier’s gun and points it at my belly, singing out, “There he is! The imperialist enemy is right here! You have to shoot him.” Everyone who is watching this scene unfold finds it hilarious. The soldier laughs so hard he cries. I get angry and leave right then. I never see or write to Abdel-Rahman again.

In May 2011, I meet this boy and his mother, walking back down Champollion Street from a protest in Tahrir. He is a young man now, and is carrying the red banner of a nascent political party calling itself the Revolutionary Youth. I introduce myself to him, but he has no recollection of ever having met me before. His mother is embarrassed to be seen with me.

July 2006. This was my first summer to get to know Dar Merit, the small, independent publishing house owned by Muhammad Hashem. Unlike other publishers in Egypt, Hashem is not afraid to publish things that might get him in trouble with the censor. Hashem is not interested in control, even though sometimes that means typos, as I found when I translated a bitter and impolite novel by the Nubian writer, Idris Ali, that Dar Merit had published.

When you go into Dar Merit, you will be asked whether you would drink coffee or tea. If you stay long enough two things will happen. First, Muhammad will roll a fat joint and pass it to you. Second, back in those days, the great Egyptian poet Ahmad Fouad Negm would probably come over around nightfall for an impromptu literary salon. I count myself very fortunate that those two things happened to me as often as I wanted that summer.

In January 2011, Dar Merit became something of a forward base of operations for young revolutionaries. Any poet or critic or artist or singer or stagehand who needed tea and a place to rest would find it at Dar Merit. Were it not for Dar Merit, we might not have any serious literary accounts of the 2011 uprising. In recent months, Mohammad Hashem has spoken about moving away from Egypt for good.

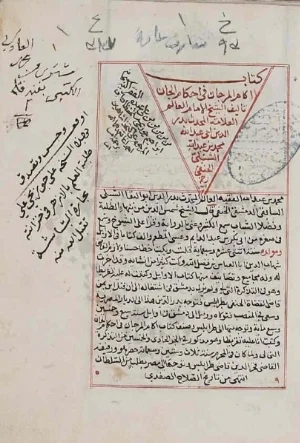

November 2012. One of the best places to buy scholarly editions of classical Arabic thought is Mutanabbi Bookshop, located on Shari‘a al-Gomhuriyya. When I go there to ask for a medieval work on jinns and afreet—Muhammad bin Abdallah al-Shibli’s Akam al-marjan fi-ahkam al-jann. The men smile politely. My question embarrasses them. “We don’t carry stuff on khurafat—superstitions,” one of them finally admits. They advise me to go to Harat al-Atrak, in the quarter behind al-Azhar University. “If you want books on superstition, you’ll find them there,” he tells me. It’s already well after dark, but I go. I get to the alley around 9PM and the shops are starting to close. I ask in one shop, and they direct me down the street. The shopkeeper is rolling down the iron door when I arrive. But he knows he has a copy and so he reopens for me. It’s not an old edition, but it is also not cheap.

By 10PM, I am sitting in a café on Champollion Street reading the book while I wait for my old friend Ahmad. He arrives around 11PM. By that time, I have gotten into the subject of jinn, where they live and their special habits and customs. As it turns out, jinn society is as developed and complicated as human society.

I am reading a chapter on how to tell if you are married to a jinn when Ahmad comes in. He is with Sabry, another old friend from the same Marxist-Leninist gang. I read to him a short passage about how jinn like to haunt bathrooms and how they can climb a stream of urine to attack a man’s penis. For the next hour, they tell me about how they knew people who had married jinn.

“Jinn are everywhere,” Ahmed said. “For instance, take ‘Old Sergeant.’ He comes walking down the street in his old wool overcoat, like he’s on patrol. You’re out there playing in the alley with your friends, and you salute him. And when he returns the salute, he accidently knocks his head off and it rolls toward you! This didn’t happen to me, but it did happen to a kid in my neighborhood when I was growing up.”

Sabry jumps in, “Or the woman who knocks on your door late at night, calling your name. She has the most beautiful voice. You crack open the door and see a woman wrapped tightly in a black shroud, her face covered, and she pleads with you with that sweet voice. She is cold and she just wants to come in and get in bed with you so she can warm up. And as soon as you open then door all the way, she rips off her veil and it’s a ghoul who wants to eat you.”

As we’re sitting there, the night drags on. My friends are sick of my questions about “the state of the revolution.” And tonight, they are grateful for the chance to talk about something else. I haven’t seen them in such a good mood for a long time. Ahmad grabs the book and skims it while we take a pause from talking. Down at the end of the street, another demonstration is getting started. Crowds of young people stream toward the Midan, others come running back trying to get away or get home, blood on their faces, tears in their eyes, clothes torn. Some are smiling and laughing, others crying. All are exhausted but somehow invigorated too. Ahmed lifts up the book and says, “Listen to this—this is about the kind of demon who lives in old ruined palaces.”

Nazik al-Mala'ika: "In the Mountains of the North"

As much as I admire Nazik al-Mala'ika's critical writing, I am not often moved by her poetry. This poem is different. It was composed while the poet was visiting the mountain hamlet of Sarsink, located in northern Dohuk province. I don't know the circumstances of the poet's residence in the village, but this poem speaks to a longing for home that is almost timeless. In Arabic, the verses have a sound pattern that are both experimental and traditional, combining a regular metrical foot ( فاعلن / فاعلن / فعلن ) with intricate and unexpected rhymes (A, B, B, A, C, C, D, D, E, D, E, F, E, F, E, G, G, H, H, H, G, G, G, G…).

In the Mountains of the North

Bring us home, O Train!

For the darkness here is terrible, and the silence is heavy.

Bring us home—the distance is vast, and the track is long,

And the nights so short.

Bring us back—the winds wail behind the shadows,

And the howling of wolves beyond the mountains,

Is like the shrieking of grief in the hearts of men.

Bring us back, for on the mountain slopes

Walks a wretched dim specter

That has left its footprints on each dawn.

The dawn of each day ends in grief and longing,

The ghost of deadly exile,

Lives in the mountains of the sad north.

The ghost of a lethal lonesomeness haunts the sad north.

Bring us back—we are fed up with wandering,

Wandering across the steep slopes.

And we go on fearing and fearing

That these evenings of absence might stretch on and on

And that the howling of wolves might bury

Our voice and make it difficult for us to come back.

Bring us back to the south,

For there, beyond the mountains, are hearts.

Bring us back to those whom we left in the fog,

Each hand beckoning, tired and despondent

Each hand is a heart.

Bring us home, O Train!—We are tired of wandering, and separation has gone on too long.

Over there is a deep whisper,

Lisping behind each road,

In the deep ravines,

Behind the clouds,

In the tremble of pine, and gaunt village,

In the jackal’s howl, in the setting stars—

There, in the pastures, a restless voice is,

A whisper telling us to return

There, other houses are

And other pastures,

And other hearts,

There, there are eyes that refuse to sleep,

And hands that gather the darkest night in a flame,

And lips that repeat our names in the gloom,

And hearts that call in pain for us to come,

And call out to the stars,

In grief and stillness,

“When, O Stars, will we be remembered by those who have fled?

And when will they come home?”

A moment. We will return.

The darkest moment of the night will not find us here, we will return.

We will return, we will cross the mountains,

And envelope the clouded peaks,

The nights of the north will not see us

Here, in this place, ever again.

The stretching expanse will not sense

The fire of our breath in the terrible night,

In the silence of the terrible night.

Bring us home, O Northern Train!

There, behind the mountains,

Delicate faces are hidden behind the nights,

Bring us home, go back to the embrace of arms,

In the shadows of date palms,

Where our past days,

In long wait,

Halted to wait,

Seeking the return of the train,

So they could travel with the travelers,

So that our days might ask those passing by,

One after another, in longing,

“When will those who fled come back?”

We should go back, for there is an old ballad there,

Around us, a whispering to return,

How I would love to go back,

After all this painful wandering

Through barren mountain ravines,

Where wolves howl.

Let’s go back—for the dark night is cold as ice,

And there, beyond the distant expanse,

Warm arms are.

Let’s return—the mountains are baring their night shadow fangs,

And there, beyond the empty night,

The voices of our loved ones in the bottomless gloom,

Throbbing with deep longing,

Their voices are heavy with the tone of blame,

These voices that the mountain passes echo,

In the silence of the place, their voices

Sing round and around like time.

Let’s go back before the adders condemn us

To a long, long separation

From the shade of the date palms,

From our dear ones behind the muteness of deserts,

Bring us home, O Train!

The nights are so short,

And there, in grief, our loved ones wait.

— Sarsink Village, Dohuk Province. 1948.

Home Does Not Exist: A Conversation with English PEN

[The following is from English PEN's series of conversations with translators of their award-winning books. Here, I am speaking with Grace Hetherington about my translation of Raba’i Al-Madhoun’s novel The Lady from Tel Aviv, which won an award in 2013.]

Grace Hetherington: The protagonist’s mother uses highly idiomatic, insulting – and often entertaining – language. How did you go about translating this into English, capturing the same effect?

Elliott Colla: This was not so easy. Walid’s mother is a strong character with a sharp tongue. What she says in Arabic is funny and also heartbreaking. It also sometimes rhymes or trips lightly across the lips. She only appears in a few scenes, so I needed to get this aspect right if I wanted to get her character right, and I needed to do it with economy and grace. The author and I went over and over these passages many times, with him telling me other stories about his mother in the process. It helped in that I have met Palestinian mothers like her. The most loving people, but strong and fierce like no one else I know. The most loving and affectionate women, but you don’t want to cross them. Each time I sat down to translate these passages I had very particular images in my mind. I imagined different friends’ mothers. More than once I felt like I had these mothers looking over my shoulder at what I was writing on the page. I knew if I got it wrong, they’d hit my hand and scowl. But if I got it right, they’d hug me and cook me the most delicious dinner I’d ever tasted.

The protagonist Walid’s story has many similarities to that of the author. Did you feel you were taking on a big responsibility translating Rabai’s personal story? Did you discuss the autobiographical elements during the translation process?

The novel overlaps significantly with the author’s own story. There’s nothing remarkable about that – but it did lead to fascinating conversations with Rabai about his life. It was not always easy to guess which aspects of the novel were autobiographical and which were fictional. The author’s own life is fantastical – if you were to read it in a novel, you would swear it was not true or not realistic. The same is true for many, many other Palestinians I have met.

The English translation of the book is subject to a noticeable editing process from the original Arabic. Is there a different approach to editing in English and Arabic publishing houses? As the translator did you help decide which bits to keep and which to omit?

There used to be a strong editorial culture in the Arab world. You read the novels of Naguib Mahfouz and it’s hard to miss. It’s there in stories of Yusuf Idris or Yusuf Sharouni. The stories are lean: almost every word or sentence is exactly where it needs to be. Unmotivated repetitions or infelicities are not to be found. At some point, this practice fell by the wayside. Nowadays, publishers usually edit for typos or grammar, but even this is not universal. Many publishing houses produce books that we would consider self-published. That does not make them bad, but it does have an impact. It’s rare that you pick up a novel in Arabic and think, every single word and sentence is there for a purpose. There are exceptions to this, and there are authors who know how to edit themselves. Ibrahim Al-Koni comes to mind – he is a perfectionist, and whatever you think about his work, you will not find mistakes in his books. But the overall impact is that a novel commercially published in Arabic is a different literary beast than a novel that has been commercially published in English. As a translator working between these two literary worlds I am very much aware of this, but I am a translator, not an editor. I had long conversations with the authors and the publisher about the editorial changes that were made to The Lady from Tel Aviv, but I was not directly involved. My job was to produce an accurate, compelling and complete translation of the novel, and that’s what I did.

Some critics have said the book’s title is misleading. Do you agree with this? Did you consider other titles?

There were many editorial changes made after I submitted the translation, which entailed about 30% of the text being removed. The publisher had, I think, perfectly justifiable reasons for making these changes, but this meant that one character and story – that of Dana Ahova – was relegated to the background. In the Arabic, the story is really almost as much about her as it is about Walid.

Describe The Lady from Tel Aviv in three words.

Home doesn’t exist.

(Original interview can be found here.)

Samih al-Qasim: "While I Walk"

One of my favorite songs of Marcel Khalife's is " منتصب قامتي أمشي " -- the words, by Samih al-Qasim, of course. Going back over his work this past week, I am struck by how important death was to his writing and thinking. It's easy to think of this song as a nationalist ballad, glorifying sacrifice, death the redeemer. Yet, listen to this song next to other nationalist songs -- or contemporary jihadist ballads -- and the differences show clear. Also, Khalife arranged this as a duet between a men's chorus and a women's chorus, back and forth. Death here is much sadder than in most songs about revolution, and the struggle for life against death reduced to a set of stark images -- an olive branch, a coffin, a red moon, a garden, rain and fire.

Here are the words:

آه آه آه آه....

منتصبَ القامةِ أمشي مرفوع الهامة أمشي

في كفي قصفة زيتونٍ وعلى كتفي نعشي

وأنا أمشي وأنا أمشي....

قلبي قمرٌ أحمر قلبي بستان

فيه فيه العوسج فيه الريحان

شفتاي سماءٌ تمطر نارًا حينًا حبًا أحيان....

في كفي قصفة زيتونٍ وعلى كتفي نعشي

وأنا أمشي وأنا أمشي

Translated, this falls flat:

Strong of stature, I walk. Head raised high, I walk.

A burst of olive in one hand, and my funeral bier on my shoulder...

The power of the poem/song lies in the repeated refrain "and I walk," whose punch comes the work being done by the letter " و " (waw). As any student of Arabic knows, "waw" means "and" though in this particular construction -- followed by an imperfective verb -- it describes an action that is ongoing, what is called a "hal clause." "Waw" means "and," but here it is better translated as "while." The refrain affirms the action of walking onwards, standing tall, carrying peace and death at the same time. It also suggests that the hero is walking on despite everything else. This sense of "carrying on despite all this" is how the song/poem articulates its unique sense of resistance, contained within the single letter "waw."

Samih al-Qasim: Two Platform Poems

Two platform poems from Samih al-Qasim.**

“Rafah’s Children” (1971)

To the one who digs his path through the wounds of millions

To he whose tanks crush all the roses in the garden

Who breaks windows in the night

Who sets fire to a garden and museum and sings of freedom.

Who stomps on songbirds in the public square.

Whose planes drop bombs on childhood’s dream.

Who smashes rainbows in the sky.

Tonight, the children of the impossible roots have an announcement for you,

Tonight, the children of Rafah say:

“We have never woven hair braids into coverlets.

We have never spat on corpses, nor yanked their gold teeth.

So why do you take our jewelry and give us bombs?

Why do you prepare orphanhood for Arab children?

Thank you, a thousand times over!

Our sadness has now grown up and become a man.

And now, we must fight.”

“Shalom” (1964)

Let someone else sing about peace,

Sing of friendship, brotherhood and harmony.

Let someone else sing about crows

Someone who will shriek about the ruins in my verses

To the dark owl haunting the debris of the pigeon towers.

Let someone else sing about peace

While the grain in the field brays,

Longing for the echo of the reapers’ songs.

Let someone else sing for peace.

While over there, behind the barbed fences

In the heart of darkness,

Tent cities cower.

Their inhabitants,

Settlements of sadness and anger

And the tuberculosis of memory.

While over there, life is snuffed out,

In our people,

In innocents, who never did any harm to life!

And meanwhile, here,

So many have poured in … so much abundance!

Their forefathers planted so much abundance for them,

And also, alas, for others.

This inheritance—the sorrows of years—belongs to them now!

So let the hungry eat their fill.

And let the orphans eat leftovers from the banquet of malice.

Let someone else sing peace.

For in my country, on its hills and in its valleys

Peace has been murdered.

------

** Translator's note:

Much of Samih al-Qasim's poetry can be called "platform poetry," following Salma Khadra al-Jayyusi's term (i.e., poetry meant for live recitation at a contentious political event). The language is direct and at times didactic. The address, though in formal Arabic, is topical and relatively uncomplicated, the images and phrases tied closely to a particular situation. Ambiguity and play, normally hallmarks of poetic discourse, are muted in this genre. Even when accurate and relatively felicitous, translating this kind of poetry into words on the page entails taking them out of that immediate situation and the context of public performance with its feedbacks and improvisations. Which is to say, this kind of poetry -- and indeed, much of al-Qasim's work -- loses much (or most) of its power when rendered into silent words on the written page. Moreover, this poetry is both rhymed and metrical in the original, but not in this translation. In this sense, these translations give a sense of some of the images and phrases of al-Qasim's poetry, but very little of the power they would have had for live audiences.

The first poem here, "Rafah's Children" ( أطفال رفح ), could have been written this month, in the wake of Israel's latest atrocities. In this way, the poem is a terrifying and uncanny reminder of Israel's violent history and how a single, out-of-date occasional poem -- composed to commemorate a particular moment of violence in the early days of Israel's occupation of Gaza -- becomes topical again when these same events repeat themselves.

I've translated the second poem, " السلام " ('Peace,' in Arabic) as "Shalom," since in this poem al-Qasim speaks to the duplicitous and patronizing idiom of "peace" and "coexistence" -- not to mention the linguistic violence of the colonizer's language, modern Hebrew -- with which Zionists have always addressed Palestinian citizens of Israel. Though the poet uses the Arabic word, al-salam, the Hebrew shalom, looms everywhere in the poem's immediate context.

Samih al-Qasim: The Last Train

The great Palestinian writer Samih al-Qasim has died. While known primarily as a poet, al-Qasim was also a talented essayist, writing regularly in the Arabic-language press of Palestine/Israel. He was also a remarkable public speaker and letter writer. His correspondence with Mahmoud Darwish instantly became a classic of Arabic epistolary literature. Truly unique in the modern canon, they are not just monuments to poetry and language, but also friendship and love.

al-Qasim addressed the following "letter" (from 1990) to the memory of a talented Palestinian poet, Rashid Hussein, whose tragic death in 1977 greatly impacted the poets of that generation. No less than the letters to Darwish, this missive shows al-Qassim at his most profound.

[Image of Letter from Rashid Hussein to Samih al-Qasim, May 18, 1970]

Rashid, my brother —

Believe it or not, but after all this time separated from one another, you may find it hard to recognize me when you stand there on the station platform, waiting for me to arrive on the last train.

I will see you when I step off that train. You will be the tallest one in the crowd waiting at the station. I will call out your name and you will come running, cigarette in mouth, as always. You will stop and stand off a bit and ask, “Is this really you? What did you do with your mad childhood? From which fire did you inherit this gray ash on your temples?”

I will tell you, “I have made my peace with death. I have swallowed the bitter colocynth of wisdom to its dregs.”

And I will say to you, “I still grieve your death.”

And you, typical of you, will try to comfort me as I mourn your passing.

O Rashid, you unhappy man, you most unlucky brother! On the thirteenth anniversary of the senseless event of your “having had enough,” I went to Musmus to pay you a visit. When you left us, I went to visit your mother. I nearly fainted when I saw her—she looked so much like my own mother! I am not talking about feelings or emotions, but a naked truth, a bare fact. For days, I was haunted by the terrifying fact of that visit.

There is something else, too: I never elegized you. I do not even know how I was supposed compose such a poem. I want you to tell me the truth: would you be angry if I wrote an elegy for you, about you? Would you consider that an unfriendly gesture, and me, the kind of friend who believed in unsubstantiated rumors?

Rashid, my brother—recently, I went through my old files. There among the papers I stumbled across several letters from you. They amazed me, but it pained me to read them. They somehow cast the light of death into my heart. Touching them left your hot ashes on my fingertips.

Your letters said, “I never came back to you. I belong to time.”

Time said, “You belong to me. And also these letters.”

I said, “So let’s belong to Rashid—like a tear in ink, like ink on paper, like paper on the wind.”

Please excuse me, my brother, my friend, my comrade. Forgive me, dear Rashid, when I offer these letters up for all to read, even though they were a part of your life that you meant for me alone.

These letters spoke to me. After you died, they told me, “I belong not to you, but to time and the wind and family.”

Is this a last letter to you? Do these words apply more to me than you? Are they a memory of a friendship that has been knocked senseless, like an olive tree hit by artillery fire?

I dispatch these words to you on two wings—on the ashes of the rose, and on the smoke of song. Can these words speak what is beyond speech?

Questions, my brother. Questions, my friend. How will we—who live in an age indentured to questions—ever become foolish enough to wait for the answers?

After death became a familiar face in my heart and around my home, I made my peace, without mercy and without bargaining.

And it seems to me that in doing this, I have also reconciled myself to life, for now we have an easier time getting along and understanding each other.

What remains of this life is less than what has passed. You and I will see each other again, because we have always chosen to meet. Even as we have been prevented from meeting as life in living, we will meet as a death in living, as a life in dying.

We will meet again. You will be waiting for me on the platform when I take the last train. You will have no trouble recognizing me.

— From Ramad al-warda dukhan al-ughniyya: Kalimat ‘an Rashid Hussein, kalimat minuh, kalimat ilayh, ed. Samih al-Qasim (Haifa: Maktabat Kull Shay’, 1990).

Grays in the Emerald City (Interview with Henry Peck)

Henry Peck of Guernica: Your novel has many elements of noir fiction—we follow a melancholy sleuth of sorts who comes up against the law, doesn’t always remember how he got home, and may be seduced by a beguiling woman. This plays out against the backdrop of the first months of US occupation in Iraq, in the second half of 2003. Why did you choose this genre of storytelling to depict this moment in Iraq?

Elliott Colla: The novel is really interested in a moment of ambiguity. Setting it in the fall of 2003 is not an accident; this is a moment that is important for us to return to, and this is what the book is asking us to do. To go back to the moment where the clarity of war, and the sharp divisions between us and them, good and evil, lovers of freedom and Baath Party, break down. And they break down precisely because the US has gotten itself into a situation of military occupation where in order to rule and to occupy it has to deal with the people it has just spent all this effort to demonize.

This is why it’s so suitable for the book to be in the noir genre—it has to do with the actual murkiness of a situation. Noir is where the clarity of moral divisions break down, the black and whites turn into grays. So as I was thinking about this particular moment of compromise on the part of the US, where it was learning how to make alliances with all sorts of Shiite groups in order to occupy, and creating all sorts of new divisions that didn’t exist before. Just as certain Cold War binaries were collapsing, new binaries of Sunni versus Shia or Arab versus Kurd were being created by the new occupation force. It’s the corruption of that moment that I am really interested in. (read on here)

![[Image of Letter from Rashid Hussein to Samih al-Qasim, May 18, 1970]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52dc0cc7e4b0e34b862ece81/1522078513376-7FOTUPI3WF1FKEC6SG7V/RHusseintoSQasim.jpg)