[Tomorrow night, I will be joining a distinguished panel of poets, activists and scholars speaking about poetical and political freedoms at George Mason University's Fall for the Book festival. This is part of an ongoing DC-wide effort to contribute to the Mutanabbi Street Starts Here DC Project. Rather than give "analysis", I thought I would talk about poetical and political freedoms by way of my relationship to the book markets of Cairo. This is what I will read tomorrow night, though more in the style of a slide show. See you there! Here's a version in Italian.]

September 1985. My first year as a student in Cairo. I visit Cairo’s main book market located in the famous area of Ezbekiyya. When Napoleon tried to conquer Egypt, this was the site of a man-made lake surrounded by the ornate palaces of Turkish Pashas and high-ranking officials of the late Mameluke state. A century later, during British rule, the lake had been filled in and the area converted into a vast entertainment district. Bars and theatres, cabarets and brothels catered to Cairo’s elites who met in this border zone located between the medieval casbah and the new colonial downtown. By the time I get to Cairo, most of this history has disappeared under flyovers and Soviet-era concrete projects. Still, a few sordid belly-dance clubs still hold out over near the decrepit old fire station and post office.

The book market is literally fastened to an old black iron fence. Inside the bars, sit the stately gardens of Ezbekiyya Park, completely off-limits to the general public. Outside, the book market stalls cling to a tiny strip between the fence, a chaotic bus depot, and the busy streets of Ataba.

I do not read Arabic in 1985. So, I mostly look around at the posters. During those years, most of them featured the Indian beefcake actor, Amitabh Bhachchan and a woman provocatively fixated on a snake, her full red lips about to kiss it.

Among the piles of used books, I find heaps of English-language books. Most are those cheap simplified editions of classics—like Wuthering Heights and Great Expectations—that fill the markets of former colonies. I find a scientific treatise entitled, Spontaneous and Habitual Abortion. The seller tells me it costs 25 piastres, maybe about 5 cents. I mumble something in pigeon Arabic and put it back, the bookseller smiles. I go back often that year.

November 1989. The Berlin Wall has fallen or is falling. Around then, the book market is removed from the fences at Ezbekiyya, during the building of the Midan Opera Metro Station. It is hard to tell whether anyone noticed. It is hard to tell if anyone cares.

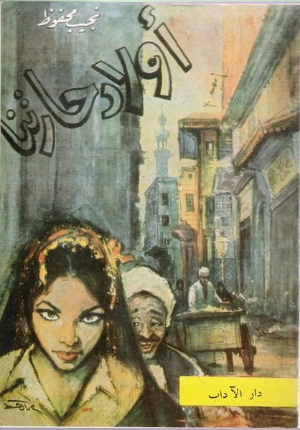

Everybody tells me I need to read Naguib Mahfouz’s novel about the death of God. The only problem is that times and mores have changed since Awlad haritna was first published. The novel originally came out in the Friday sections of al-Ahram in the late 1950s. Now it is banned in Egypt, deemed controversial and un-Islamic.

Everybody tells me that I can find the novel if I go to Madbuli's Bookshop in Midan Talaat Harb and ask for it discreetly. I go there and linger suspicious around the various sections of the bookstore. It’s like I’m looking for porn. Different employees come to ask if they can help. Finally, I gather up the courage and say, “They tell me you have copies of Awlad Haritna.” The man doesn’t even look at me. He mutters, “They’re wrong, whoever 'they' are,” and he keeps dusting the pile of books in front of him.

June 1990. The cold war is over, but Saddam Hussein has yet to invade Kuwait. I still want to find a copy of Mahfouz’s novel. I go back to Madbuli’s one afternoon. As soon as I enter, a skinny young man about my age asks if he can help me. I casually mention the title, and say nothing else. He disappears into the back and emerges with a book in a plastic bag. “Anything else?” He smiles at me. For the next 23 years, Ashraf becomes one of the first people I see whenever I return to Cairo. For the last six years, he makes a point of always asking about my daughter, even though he has yet to meet her.

February 1991. The new world order has begun, and three Cairo University students are killed protesting Mubarak’s decision to lend support to American troops. During these months, I have a standing date on Friday afternoons to meet a friend, Ahmad. We meet at the used book stalls just off Midan Sayyida Zeinab. I begin to find lots of books I need for my studies. I find a complete run of the literary magazine Fusul. And lots of old issues of al-Tali‘a. I find classics of literary criticism, 1950s editions when scholarly publishers like Dar al-Ma‘arif had editors. Ahmad and I wander among the stalls for an hour or so, then go off to a café just off the square where we discuss the reading he has assigned me for the week. For months, I have been reading Louis Althusser under Ahmad's tutelage. Later, when I return to graduate seminars in Berkeley, his lessons stand me in good stead.

January 1994. Cairo Book Fair. An annual event when all the publishers of the Arab world, and all the booksellers of the city, bring their wares out to a Soviet-era fairground for hosting industrial expositions in Medinat Nasr. It’s as cold and gray as ever, a day for drinking hot tea. I go out there with a group of leftist friends. We are all proudly wearing the same thick wool overcoats we bought in the outdoor market behind Ramses Station. Before we get there, Ahmed shows off the multiple hidden pockets his sister sewed into the lining. We spend the day wandering around the Moroccan publishers’ tables, where the most interesting stuff is being sold. Ahmed fills his pockets. We visit some of the salons where poets and critics and philosophers debate topics of the day. A group of Egyptian literary critics sit on a panel and discuss the Libyan Brother Leader’s collection of short stories entitled, The Village, the Village! The Land, the Land! We laugh as some critics talk about how sophisticated Qaddafi’s writing is. We wonder how much they were paid. We look around, but Ahmed is not with us. Later on, we learn he has been arrested for shoplifting. He tried to run away when they caught him, but his coat had more than 30 books in it.

June 1995. I find out that the Ezbekiyya book markets had been relocated some time ago back behind al-Azhar University, in the neighborhood of al-Bataniyya. In 1985, hashish was openly sold in the streets of Bataniyya, and was more affordable than beer. The sellers are gone now. To get to the used book market you can either enter from Harat al-Atrak, a small street filled with religious bookstalls, turning right toward the old city walls, now vast piles of medieval rubble. Or you can take a taxi to the end of Azhar Street, getting off at the Benetton, and walking to the right until you find the market. I find a treasure the first time I go there: an incomplete 19th century lithograph edition of al-Maqrizi’s Khitat. But the volume I need for my dissertation research is there. Because it’s incomplete, the seller subsequently negotiates a huge discount for me with the bookbinder.

March 1998. At some point, the Ezbekiyya book market has moved back to a newly renovated space in Ezbekiyya, back by the National Theatre. Friends introduce me to Mustafa Sadeq, a well-regarded book merchant in the market. We sit down and he listens to me as I describe the kinds of books I am interested in for a project on the representation of women and prostitution in Egyptian literature. Each week I come back, he has found a new pile of titles for me to peruse, most not related to what I am working on, but some very much so. He tells me he has a stash of books for me in his storehouse and invites me to come over there. It’s located in an alley in the Hilmiyya neighborhood, not far from where I used to study Althusser on Fridays.

Mustafa Sadek is waiting from me when I arrive. He rolls open the iron door and we step inside. He points to a stack of dusty old magazines and journals. I look at the first magazine and can’t believe it. I thumb through pages of erotic stories that are accompanied by photographs of naked women in suggestive poses. I look at the date on the periodical: 1934. I look at the next, same thing. And then more. Finally, I look up and find him smiling at me. “I know you are not only researching literature but also some impolite things,” he says with a sly smile.

The trove costs me every thing I had in my wallet, and still I owe Mustafa. On my way home, I go to meet Shehata —an Egyptian poet and novelist—for tea. I pull out all the nudie magazines I’ve just purchased and say, “Can you believe this?!” “I never knew this stuff existed,” he murmurs over and over. “This is an important source. We need to do something serious with this. Can I borrow this and show it to an editor. Together we might figure out a way to republish this as a historical document.” I wrap up the magazines for Shehata. We agree to meet up, as we always do, a couple days later. Shehata doesn’t come, and he stops answering my emails. Years later, when I finally see him again, he apologizes for disappearing. He was in the midst of a messy divorce. When I ask about the magazines, he claims he gave them back to me. I never see them again.

July 2002. Some old classmates from Cairo University have opened a great bookstore— Sindbad—located just behind the Cosmopolitan Hotel in the revitalized Bourse neighborhood. I go there and browse for hours. Despite its tiny size, this bookshop holds more treasures than the bigger stores around the corner. One afternoon, I am sitting with Abdel-Rahman S.—brilliant brother of the brilliant Muhammad S.—who is now not just a professor at Cairo University, but also one of the principal shareholders in Sindbad. He and his wife had just had me over for lunch a couple days earlier, and we’re sitting around talking while waiting for our old professor—Egypt’s leading left literary critic—to meet us there. The subject now, as before, is American imperialism and the efforts of Egyptian intellectuals and artist to boycott Israel. Abdel-Rahman’s rambunctious and precocious eight-year-old son is with us all afternoon, bored out of his mind, entertaining us by asking questions that go beyond his years. At some point, the kid starts referring to me as the “imperialist, colonialist American,” and everyone laughs. He disappears. Minutes later, Abdel-Rahman and I go out to find the boy. We watch him walking down the pedestrian mall pulling on an Egyptian conscript who had been stationed outside the bank on the corner. The boy points at me and calls out, “See! See! Fire! Fire!” The soldier doubles over in laughter, not able to believe his eyes when he sees the boy has produced the Zionist enemy he had promised. By the time we arrive, the boy has grabbed the soldier’s gun and points it at my belly, singing out, “There he is! The imperialist enemy is right here! You have to shoot him.” Everyone who is watching this scene unfold finds it hilarious. The soldier laughs so hard he cries. I get angry and leave right then. I never see or write to Abdel-Rahman again.

In May 2011, I meet this boy and his mother, walking back down Champollion Street from a protest in Tahrir. He is a young man now, and is carrying the red banner of a nascent political party calling itself the Revolutionary Youth. I introduce myself to him, but he has no recollection of ever having met me before. His mother is embarrassed to be seen with me.

July 2006. This was my first summer to get to know Dar Merit, the small, independent publishing house owned by Muhammad Hashem. Unlike other publishers in Egypt, Hashem is not afraid to publish things that might get him in trouble with the censor. Hashem is not interested in control, even though sometimes that means typos, as I found when I translated a bitter and impolite novel by the Nubian writer, Idris Ali, that Dar Merit had published.

When you go into Dar Merit, you will be asked whether you would drink coffee or tea. If you stay long enough two things will happen. First, Muhammad will roll a fat joint and pass it to you. Second, back in those days, the great Egyptian poet Ahmad Fouad Negm would probably come over around nightfall for an impromptu literary salon. I count myself very fortunate that those two things happened to me as often as I wanted that summer.

In January 2011, Dar Merit became something of a forward base of operations for young revolutionaries. Any poet or critic or artist or singer or stagehand who needed tea and a place to rest would find it at Dar Merit. Were it not for Dar Merit, we might not have any serious literary accounts of the 2011 uprising. In recent months, Mohammad Hashem has spoken about moving away from Egypt for good.

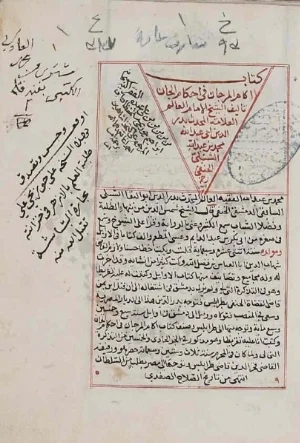

November 2012. One of the best places to buy scholarly editions of classical Arabic thought is Mutanabbi Bookshop, located on Shari‘a al-Gomhuriyya. When I go there to ask for a medieval work on jinns and afreet—Muhammad bin Abdallah al-Shibli’s Akam al-marjan fi-ahkam al-jann. The men smile politely. My question embarrasses them. “We don’t carry stuff on khurafat—superstitions,” one of them finally admits. They advise me to go to Harat al-Atrak, in the quarter behind al-Azhar University. “If you want books on superstition, you’ll find them there,” he tells me. It’s already well after dark, but I go. I get to the alley around 9PM and the shops are starting to close. I ask in one shop, and they direct me down the street. The shopkeeper is rolling down the iron door when I arrive. But he knows he has a copy and so he reopens for me. It’s not an old edition, but it is also not cheap.

By 10PM, I am sitting in a café on Champollion Street reading the book while I wait for my old friend Ahmad. He arrives around 11PM. By that time, I have gotten into the subject of jinn, where they live and their special habits and customs. As it turns out, jinn society is as developed and complicated as human society.

I am reading a chapter on how to tell if you are married to a jinn when Ahmad comes in. He is with Sabry, another old friend from the same Marxist-Leninist gang. I read to him a short passage about how jinn like to haunt bathrooms and how they can climb a stream of urine to attack a man’s penis. For the next hour, they tell me about how they knew people who had married jinn.

“Jinn are everywhere,” Ahmed said. “For instance, take ‘Old Sergeant.’ He comes walking down the street in his old wool overcoat, like he’s on patrol. You’re out there playing in the alley with your friends, and you salute him. And when he returns the salute, he accidently knocks his head off and it rolls toward you! This didn’t happen to me, but it did happen to a kid in my neighborhood when I was growing up.”

Sabry jumps in, “Or the woman who knocks on your door late at night, calling your name. She has the most beautiful voice. You crack open the door and see a woman wrapped tightly in a black shroud, her face covered, and she pleads with you with that sweet voice. She is cold and she just wants to come in and get in bed with you so she can warm up. And as soon as you open then door all the way, she rips off her veil and it’s a ghoul who wants to eat you.”

As we’re sitting there, the night drags on. My friends are sick of my questions about “the state of the revolution.” And tonight, they are grateful for the chance to talk about something else. I haven’t seen them in such a good mood for a long time. Ahmad grabs the book and skims it while we take a pause from talking. Down at the end of the street, another demonstration is getting started. Crowds of young people stream toward the Midan, others come running back trying to get away or get home, blood on their faces, tears in their eyes, clothes torn. Some are smiling and laughing, others crying. All are exhausted but somehow invigorated too. Ahmed lifts up the book and says, “Listen to this—this is about the kind of demon who lives in old ruined palaces.”